‘Standardised testing has swelled and mutated, like a creature in one of those old horror movies, to the point that it threatens to swallow our schools whole.’

Alfie Kohn, 2000

This was the dramatic – some might argue hyperbolic – opening to American academic Alfie Kohn’s ‘The Case Against Standardised Testing‘ (sub-title ‘Raising the Scores, Ruining the Schools’), published in the USA as long ago as the year 2000, but for those who accused him of scaremongering, and for the Scottish Government, which recently pledged to re-introduce standardised testing at regular intervals in the school-life of every young person growing up in Scotland, it is worth considering 15 years down the line whether Kohn’s fears have been vindicated, or whether the focus on tests really has improved the school experience, and performance, of young Americans.

First of all, let me summarise what I believe to be the main reasons for Kohn’s opposition to standardised tests, although I should point out that while he believes standardised testing to be a thoroughly bad idea, some forms of standardised testing are regarded as slightly less bad than others. I would also acknowledge that in summarising his position, one runs the risk of over-simplifying the case. As always, there is no substitute for buying the book and reading it in full, including the list of references and the research behind his conclusions.

First of all, let me summarise what I believe to be the main reasons for Kohn’s opposition to standardised tests, although I should point out that while he believes standardised testing to be a thoroughly bad idea, some forms of standardised testing are regarded as slightly less bad than others. I would also acknowledge that in summarising his position, one runs the risk of over-simplifying the case. As always, there is no substitute for buying the book and reading it in full, including the list of references and the research behind his conclusions.

- Standardised tests create the ‘illusion’ of objectivity. The results of the tests may sound scientific, since they are assigned a numerical score, but the reality is that they are set by adults who have an assumed ‘correct answer’ in mind, and taken by children with hugely differing experiences and attitudes, even on test day. It is not possible to remove subjectivity from the process.

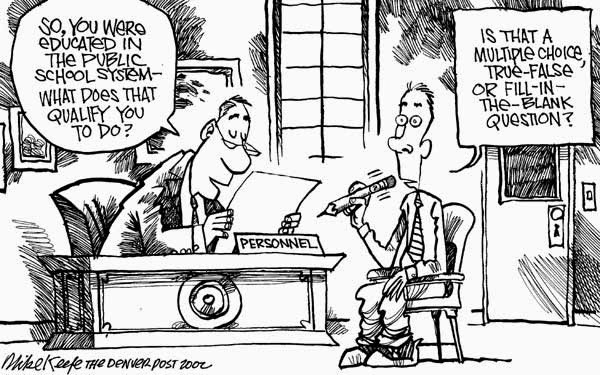

- Standardised tests are no indicator of ability. If the justification for standardised tests is that we need to know what someone is capable of doing, there are very few less reliable ways of measuring that than a paper-and-pencil test, where the tasks are kept secret until the last minute. It is difficult to find examples of this kind of test being replicated in real life situations.

- Standardised tests tell us what we already know. The main thing standardised test scores tell us is how big students’ houses are. Research tells us that socio-economic factors (the amount of poverty in communities where schools are located) is the biggest factor in the variation of test scores from one area to another. To suggest therefore that standardised test scores are going to close an ‘attainment gap’ is demonstrably false.

- Standardised tests are mainly a test of memory. In the worst kind of standardised tests – those where children are asked to choose the right answer from a selection of possible answers – choosing the right answer gives no indication of understanding. Most standardised tests take no account of how an answer was arrived at, and bear no resemblance to problems faced in the real world.

- Standardised tests are designed to separate children into categories. The ultimate goal of standardised tests is not to evaluate how children have been taught, or how well they have learned. If a certain question is included in a trial paper and almost everyone gets it right – or if almost everyone gets it wrong – it will almost certainly be chucked out. Remember, the goal is not to test what has been learned, but to separate and categorise.

- Standardised tests teach kids (and teachers) the wrong lessons. When tests are given a status above all else in the education system, they contribute to the ‘already pathological competitiveness’ of the culture. The process of schooling becomes more about winning than learning, and we see others as barriers to our own success. In addition, an emphasis on remembering facts encourages a ‘pub quiz’ view of intelligence that confuses being smart with knowing loads of stuff.

- Standardised tests encourage the view that learning is something you do on your own. Tests are given to individuals, and supporting each other is known as ‘cheating’. In real life, learning is something we do with (and for) each other. Standardised tests don’t measure co-operation, collaboration, effort, empathy……..

- Standardised tests have inaccuracies built into them. Even when they are scored correctly, and meet the required standards for reliability, many children end up being ‘misclassified’ because of the limits of test accuracy.

- Standardised tests do not lead to greater accountability. A common justification for using standardised tests is that there are poor teachers out there and we need to find out who they are. This is based on a flawed logic. First of all, even if you believe that teachers are responsible for their students’ results, it would be irrational to hold a teacher responsible for the results of children who have recently arrived in his or her class. Secondly, and paradoxically, the test-driven teaching which results from the introduction of standardised tests actually reinforces what the worst teachers have been doing all along.

- Standardised tests stifle creativity. In an environment where high-stakes testing prevails, teachers become defensive and competitive, making sure everyone knows that low test scores were not their fault. Teaching to the test becomes the norm, and activities which don’t appear to contribute to test preparation are curtailed.

- Standardised tests narrow the conversation about education. The more that scores are emphasised, the less discussion there is about the goals of education. The content and the pedagogy of the school are adversely affected; the tests effectively become the curriculum. Spontaneity is discouraged, interesting pathways ignored. Children’s social, moral and intellectual development is put on hold.

- Standardised tests are educationally damaging. As teachers are encouraged not only to spoon-feed students the facts they will need to pass the tests, but to provide them with ‘test-taking’ skills, such as skimming a text rather than reading it deeply and reflectively, they spend less time helping them to become ‘critical, creative, curious thinkers’.

- Standardised tests don’t ‘raise standards‘. When teachers and students are forced to focus on only those things which can be reduced to numbers, such as how many grammatical errors are present in a piece of writing, the process of thinking has been effectively relegated to a lesser importance. As the saying goes, we are then valuing what we can measure, rather than measuring what we value.

- Standardised tests discriminate against poorer children and parents. When the stakes are high, parents and schools use whatever means they can to achieve better results, which usually means buying more and better test preparation materials, or access to tutors and extra tuition. When schools decide to buy ‘reading schemes’ for example, as a quick fix, it is often at the expense of more exciting and interesting books and materials. The result is a narrowing of the learning experience generally for children in deprived areas.

‘Testing allows politicians to show they’re concerned about school achievement and serious about getting tough with students and teachers. Test scores offer a quick-and-easy – although, as we’ll see, by no means accurate – way to chart progress. Demanding high scores fits nicely with the use of political slogans like ‘tougher standards’ or ‘accountability’ or ‘raising the bar’.

Alfie Kohn, 2000

Conventional wisdom used to have it that top U.S. students did well compared to their peers across the globe, when adjustments were made for higher poverty levels and racial diversity, but even allowing for these factors the latest available PISA test results, released in December 2013, showed that the best-performing U.S. students were falling behind even average students in Asian countries (or sub entities), which now dominate the top 10 in maths, reading and science. (source). In other words, even in the ‘pro-testers’ world’ and using the success criteria preferred by the pro-testing lobby, the relentless focus on testing does not appear to help kids perform better in standardised tests! It is of little surprise therefore that many leading academics are now questioning the validity of The PISA tests themselves, and the propensity for governments around the world to use them in determining educational policy (source). The key findings of that 2013 report demonstrate that not only were the serially-tested American youngsters failing to make any headway in global comparisons, but that the testing regime was having a damaging effect on their ability to think for themselves and apply their learning in real-life situations.

PISA 2012 Key Findings USA

- Among the 34 OECD countries, the United States performed below average in mathematics in 2012 and is ranked 27th (this is the best estimate, although the rank could be between 23 and 29 due to sampling and measurement error). Performance in reading and science are both close to the OECD average. The United States ranks 17 in reading, (range of ranks: 14 to 20) and 20 in science (range of ranks: 17 to 25). There has been no significant change in these performances over time.

- Mathematics scores for the top-performer, Shanghai-China, indicate a performance that is the equivalent of over two years of formal schooling ahead of those observed in Massachusetts, itself a strong-performing U.S. state.

- While the U.S. spends more per student than most countries, this does not translate into better performance. For example, the Slovak Republic, which spends around USD 53 000 per student, performs at the same level as the United States, which spends over USD 115 000 per student.

- Just over one in four U.S. students do not reach the PISA baseline Level 2 of mathematics student proficiency – a higher-than-OECD average proportion and one that hasn’t changed since 2003. At the opposite end of the proficiency scale, the U.S. has a below-average share of top performers.

- Students in the United States have particular weaknesses in performing mathematics tasks with higher cognitive demands, such as taking real-world situations, translating them into mathematical terms, and interpreting mathematical aspects in real-world problems.

- Socio-economic impact has a significant on student performance in the United states, with some 15% of the variation in student performance explained by this, similar to the OECD average. Although this impact has weakened over time, disadvantaged students show less engagement, drive, motivation and self-belief.

- Students in the U.S. are largely satisfied with their school and view teacher-student relations positively. But they do not report strong motivation towards learning mathematics: only 50% of students agreed that they are interested in learning mathematics, slightly below the OECD average of 53%.

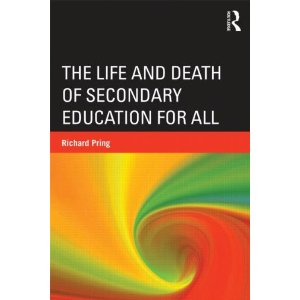

This week, the first signs appeared that America is about to admit that it got it wrong with George Bush’s inappropriately named ‘No Child Left Behind‘ reforms, when President Obama called for a reduction in testing in American schools (New York Times story), and a warning is issued today to the Scottish Government in the form of a report for the newly-formed left-wing political alliance, RISE. ‘Placing Our Trust in the Teaching Profession: The Case Against National Standardised Testing‘ uses several international studies to show that, far from reducing the attainment gap in education, the introduction of high-stakes national tests may well have the exact opposite effect.

Similarly, in its ‘Book of Ideas‘, the Scottish independent ‘think and do tank’ Common Weal had this to say to politicians seeking election to Holyrood next May:

‘But education should, at heart, be about improving our quality of life. This can mean many things. It can mean exposing ourselves to ideas and thoughts which expand how we see ourselves and our lives. It can mean learning coping skills to help us respond positively to the things that happen to us throughout our lives. It can mean giving us the skills to do the things we enjoy. It certainly means making us feel good about ourselves as valuable members of society. It certainly shouldn’t mean creating a system driven by the need to pass exams as a means of avoiding a bad life. The cycle of pressure and anxiety that an educational regime driven by testing exerts has been shown to change the brain chemistry of children and can affect them throughout their lives. You cannot test a child into being a happy, constructive and productive citizen.’

ourselves to ideas and thoughts which expand how we see ourselves and our lives. It can mean learning coping skills to help us respond positively to the things that happen to us throughout our lives. It can mean giving us the skills to do the things we enjoy. It certainly means making us feel good about ourselves as valuable members of society. It certainly shouldn’t mean creating a system driven by the need to pass exams as a means of avoiding a bad life. The cycle of pressure and anxiety that an educational regime driven by testing exerts has been shown to change the brain chemistry of children and can affect them throughout their lives. You cannot test a child into being a happy, constructive and productive citizen.’

We have a government in Scotland which is enjoying unprecedented popularity, and which has worn its ‘progressive’ label as a badge of honour when others have sought to use it as a term of abuse. As far as the education system is concerned, the next few months will certainly put that commitment to progress to the test.

Further Reading:

The Guardian: Obama Calls For Cuts to Schools’ Standardized Testing Regimens

Diane Ravitch: The Badass Teachers Association Respond To Testing Announcement

Andy Hargreaves and Dennis Shirley: The Coming Age of Post-Standardization

There is an episode in the American hit TV series

There is an episode in the American hit TV series  Roland Pryzbylewski’s plight came back to me this week as I finished reading

Roland Pryzbylewski’s plight came back to me this week as I finished reading